HTF has consistently opposed the Honolulu Area Rapid Transit (HART) overhead fixed guideway.

The 21-station steel-on-steel system is a resource disaster. It degrades and destroys natural and aesthetic resources while costing taxpayers an enormous sum of money. It is not so much a transportation project as a development project.

The 21-station steel-on-steel system is a resource disaster. It degrades and destroys natural and aesthetic resources while costing taxpayers an enormous sum of money. It is not so much a transportation project as a development project.

2019 Audit Reports

Audit of the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation: Report 1

Office of the Auditor, State of Hawaii

January 2019

Read online

Download report 1

Office of the Auditor, State of Hawaii

January 2019

Read online

Download report 1

Audit of the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation: Report 2

Office of the Auditor, State of Hawaii

January 2019

Read online

Download report 2

Office of the Auditor, State of Hawaii

January 2019

Read online

Download report 2

Follow-Up Audit of the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation, Resolution 17-199, CD1

Office of the City Auditor

January 2019

Read online

Download report

Office of the City Auditor

January 2019

Read online

Download report

Transit Oriented Development

A transit-oriented development (TOD) is a mixed-use residential and commercial area designed to maximize access to public transport, and often incorporates features to encourage transit ridership.

A TOD neighborhood typically has a center with a transit station or stop (train station, metro station, tram stop, or bus stop), surrounded by relatively high-density development with progressively lower-density development spreading outward from the center.

TODs generally are located within a radius of one-quarter to one-half mile from a transit stop, as this is considered to be an appropriate scale for pedestrians, thus solving the last mile problem.

A TOD neighborhood typically has a center with a transit station or stop (train station, metro station, tram stop, or bus stop), surrounded by relatively high-density development with progressively lower-density development spreading outward from the center.

TODs generally are located within a radius of one-quarter to one-half mile from a transit stop, as this is considered to be an appropriate scale for pedestrians, thus solving the last mile problem.

TOD (Transit Oriented Development) is a mixed-use residential/retail/commercial area designated to maximize access to public transportation rail and bus stops, which are surrounded by intense uses and high-density development and redevelopment. TODs generally are located within a radius of one-quarter to one-half mile from a transit stop, as noted by the pink circles.

Halawa Area Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Plan. City and County of Honolulu Resolution 17-315.

Halawa Area Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Plan. City and County of Honolulu Resolution 17-315.

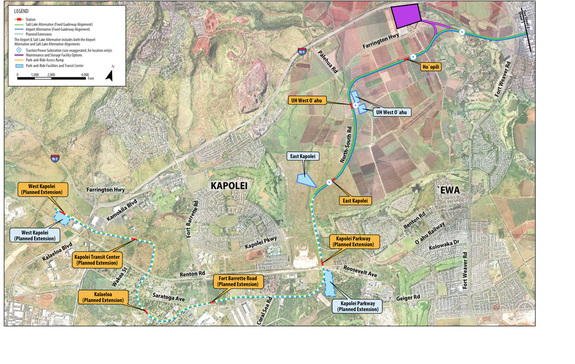

Stop Rail at Middle Street

|

HTF supports stopping the rail at Middle Street, with the hopes that decision-makers will seriously consider alternatives and not run elevated rail through downtown Honolulu.

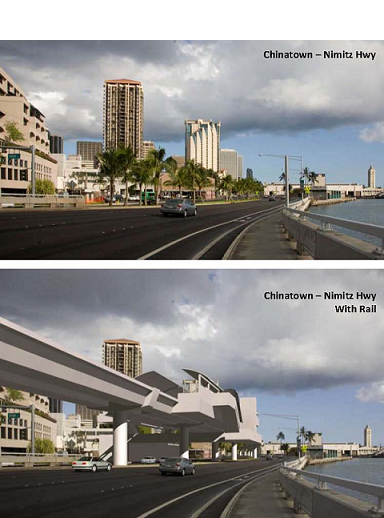

Building elevated rail through downtown Honolulu would create enormous construction impacts since entire roadways will need to be cut open to pour underground spread foundations to support the weight of the elevated guideway. Constructing the football-field sized stations planned for elevated rail would create immense disruption to nearby structures, traffic and businesses downtown. Building elevated rail through downtown Honolulu is fraught with engineering challenges and unforeseen conditions. The ground makai of Richards Street (including Nimitz Highway) is fill material, not soil or rock you can rest a lot of weight on. The existing buildings downtown were not built using simple pilings as per average construction. Read more at www.stoprailatmiddlestreet.org/ |

Rendering of street level rail on Hotel Street.

|

Fact Sheets |

FTA Correspondence |

Street Level Rail Is...

Easily accessible from street level without the need for elevators or ramps.

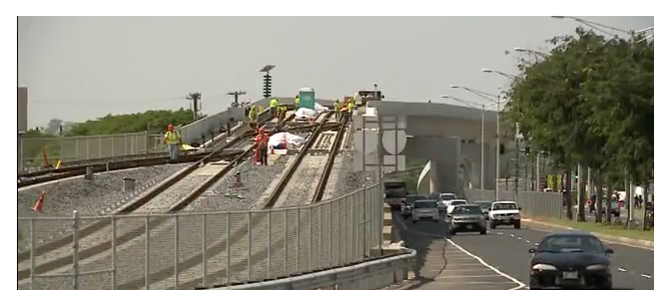

Existing Waipahu ramp shows ease of transition between street level and elevated.

More about Rail

|

|

HTF was a litigant in the Federal Court suit that attempted to stop the project.

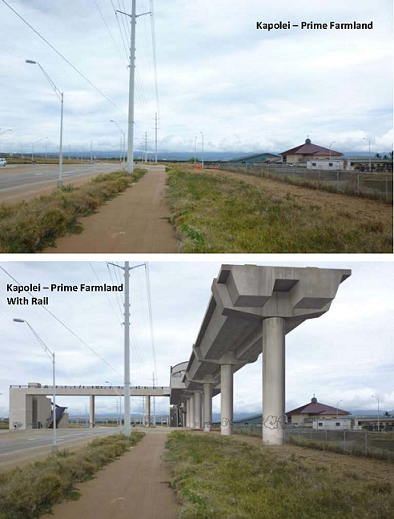

HTF has been involved in exposing the damage to the underground and cultural resources of Leeward Oahu. HTF continues to advocate for stopping overhead construction outside the Chinatown, Downtown, and Civic Center area. Kalaeloa (former Barbers Point).

|

Rail Impact on Kapolei Agricultural Lands

2016 Audit of HART

City and County Auditor

Audit of the Honolulu Authority For Rapid Transportation (HART)

Report No. 16-03 to the Mayor and the City Council of Honolulu

April 2016

Download the full audit

Audit of the Honolulu Authority For Rapid Transportation (HART)

Report No. 16-03 to the Mayor and the City Council of Honolulu

April 2016

Download the full audit

HART’s financial and operating plans are not reliable or current . . . Absent the improvements, we anticipate additional shortfalls and cost overruns will occur.” (Pg. 5)

Facts About the Rail

By Randall Roth

Rail was supposed to cost $3 billion … then $4.6 billion … then $5.2 billion. The latest official estimate is $8.1 billion … but the city reportedly is thinking about raising it to $9.5 billion.

The city’s latest upper-bound estimate is $10.8 billion. As that term is defined, there is only a 10 percent chance of costs reaching the upper-bound estimate. Two years ago, that estimate was $7.6 billion.

The Federal Transit Administration advises against building rail unless money is set aside annually to ensure safety and reliability in future years. Based on experiences elsewhere, the minimum annual contribution should be $100 million.

Actual ridership on recent rail projects around the country has averaged 40 percent less than had been predicted. The last elevated system built achieved ridership that was 75.9 percent less than had been projected. The consultant who prepared that projection, Parsons Brinkerhoff, also prepared ours.

The city claims that the percentage of commuters who use public transportation will increase from 6 percent to 7.4 percent once rail has been built. But most cities have experienced a decline in bus ridership as money is diverted from the existing bus system to pay for rail operations and maintenance. The combined rate for bus and rail is usually less than was the rate for just the bus.

For example, public transit’s share of all commuting in Atlanta was 9.1 percent before rail was added in 1979; today it’s less than 5 percent. The rate in Baltimore before it added rail in 1984 was 12.3 percent; today it’s less than 8 percent. Portland went from 9.8 percent in 1986 to less than 8 percent today.

In the months leading up to our 2008 ballot referendum, the city spent millions promoting rail as a traffic solution. A Honolulu Advertiser/Ward survey found that three out of four people believed this claim. The city’s director of transportation later admitted in the environmental impact statement that “traffic congestion will be worse in the future with rail than what it is today.”

Rail is scheduled to run 20 hours a day, but be virtually empty at times other than rush hour. Based on U.S. Department of Transportation data, rail on Oahu will consume twice as much energy per-passenger-mile than does the existing bus system. Rail’s per-passenger-mile energy use will even exceed the energy use of those who commute alone in their cars.

Steel-on-steel elevated systems make uniquely irritating sounds, particularly as the heavy cars accelerate and decelerate from 0 to 60 and back to 0 between stations sometimes only a half-mile apart.

As for unsightliness: The Outdoor Circle has described heavy rail as a scar on the face of our beautiful island.

The local chapter of the American Institute of Architects was so taken aback by heavy rail’s ugliness that it created renderings it believes are more accurate than what the city has provided. Most audiences audibly gasp when shown these as part of a PowerPoint presentation.

The federal lawsuit to stop rail gave the plaintiffs access to FTA’s internal email, which revealed intra-FTA concerns about the city’s “lousy practices of public manipulation,” use of “inaccurate statements,” culture of “never [having] enough time to do it right, but lots of time to do it over,” and an observation that the city had put itself in a “pickle” by setting unrealistic start dates for construction.

It’s not too late to convert the existing guideway to use by bus rapid transit. Some of the saved money could then be used to reduce traffic congestion, such as by installing flyovers and bypasses in chokepoint areas like the Middle Street merge; adding new contra-flow and bus-on-shoulder options; adding new traffic lanes to existing roads; and expanding Honolulu’s bus system, such as by increasing the number of express buses that go where commuters want to go, rather than eliminating most of them, as is part of the current rail plan.

A longer footnoted version of this commentary can be found at http://randallroth.com/files/Rail%20Speech.pdf.

Randall Roth is a professor of law at the University of Hawaii School of Law.

The city’s latest upper-bound estimate is $10.8 billion. As that term is defined, there is only a 10 percent chance of costs reaching the upper-bound estimate. Two years ago, that estimate was $7.6 billion.

The Federal Transit Administration advises against building rail unless money is set aside annually to ensure safety and reliability in future years. Based on experiences elsewhere, the minimum annual contribution should be $100 million.

Actual ridership on recent rail projects around the country has averaged 40 percent less than had been predicted. The last elevated system built achieved ridership that was 75.9 percent less than had been projected. The consultant who prepared that projection, Parsons Brinkerhoff, also prepared ours.

The city claims that the percentage of commuters who use public transportation will increase from 6 percent to 7.4 percent once rail has been built. But most cities have experienced a decline in bus ridership as money is diverted from the existing bus system to pay for rail operations and maintenance. The combined rate for bus and rail is usually less than was the rate for just the bus.

For example, public transit’s share of all commuting in Atlanta was 9.1 percent before rail was added in 1979; today it’s less than 5 percent. The rate in Baltimore before it added rail in 1984 was 12.3 percent; today it’s less than 8 percent. Portland went from 9.8 percent in 1986 to less than 8 percent today.

In the months leading up to our 2008 ballot referendum, the city spent millions promoting rail as a traffic solution. A Honolulu Advertiser/Ward survey found that three out of four people believed this claim. The city’s director of transportation later admitted in the environmental impact statement that “traffic congestion will be worse in the future with rail than what it is today.”

Rail is scheduled to run 20 hours a day, but be virtually empty at times other than rush hour. Based on U.S. Department of Transportation data, rail on Oahu will consume twice as much energy per-passenger-mile than does the existing bus system. Rail’s per-passenger-mile energy use will even exceed the energy use of those who commute alone in their cars.

Steel-on-steel elevated systems make uniquely irritating sounds, particularly as the heavy cars accelerate and decelerate from 0 to 60 and back to 0 between stations sometimes only a half-mile apart.

As for unsightliness: The Outdoor Circle has described heavy rail as a scar on the face of our beautiful island.

The local chapter of the American Institute of Architects was so taken aback by heavy rail’s ugliness that it created renderings it believes are more accurate than what the city has provided. Most audiences audibly gasp when shown these as part of a PowerPoint presentation.

The federal lawsuit to stop rail gave the plaintiffs access to FTA’s internal email, which revealed intra-FTA concerns about the city’s “lousy practices of public manipulation,” use of “inaccurate statements,” culture of “never [having] enough time to do it right, but lots of time to do it over,” and an observation that the city had put itself in a “pickle” by setting unrealistic start dates for construction.

It’s not too late to convert the existing guideway to use by bus rapid transit. Some of the saved money could then be used to reduce traffic congestion, such as by installing flyovers and bypasses in chokepoint areas like the Middle Street merge; adding new contra-flow and bus-on-shoulder options; adding new traffic lanes to existing roads; and expanding Honolulu’s bus system, such as by increasing the number of express buses that go where commuters want to go, rather than eliminating most of them, as is part of the current rail plan.

A longer footnoted version of this commentary can be found at http://randallroth.com/files/Rail%20Speech.pdf.

Randall Roth is a professor of law at the University of Hawaii School of Law.